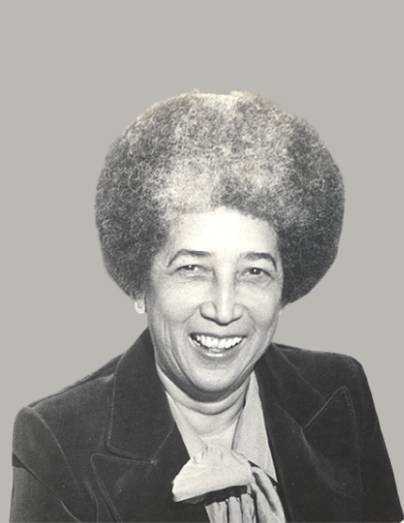

Antonia Pantoja

Antonia Pantoja was a formidable figure in the historical development of Puerto Rican and Latinx life in New York, Puerto Rico, California, and beyond during the second half of the 20th century. A black, queer, Puerto Rican educator, social worker, and foundational figure in the Puerto Rican community in postwar New York City, Pantoja established several groundbreaking institutions in New York and in Puerto Rico. Her goal was to enhance civil rights and educational opportunities and to promote positive imagery and self-love for Puerto Ricans in New York and beyond. She is best known for establishing the organization ASPIRA in 1961, an important organization that promoted education and advancement for Puerto Rican youth in New York City by providing clubs within schools, career and college counseling, advocacy for bilingual education, and other services.

Pantoja was born on September 13, 1922, in San Juan, Puerto Rico, to an impoverished family of laundry and tobacco workers. She earned her teaching degree from the University of Puerto Rico with help from wealthy neighbors. When she arrived in New York in 1944, she took a job as a wartime welder in a factory that made children’s lamps, where she also helped unionize the workers in her shop. She obtained a scholarship to study at Hunter College and then a master’s degree in social work from Columbia University. Pantoja later received a Ph.D. from Union Graduate School (now Union Institute & University) in Cincinnati, Ohio. Her academic work centered around experimental higher education in the United States.

Her life’s work revolved around educational access for the disadvantaged and community self-determination. Pantoja’s lifelong mission was to empower community members to speak for themselves.

Dr. Pantoja’s professional life spans a period that includes many of the most important political, social, and economic changes and upheavals in the postwar history of the United States, New York City, and her native Puerto Rico. When she left Puerto Rico at the end of the Second World War, the island was at the beginning of a momentous transitional period that resulted in a profound political and economic restructuring of its relationship with the United States.

Pantoja arrived in New York City while the city was at war, its economy having been rewired to accommodate and contribute to the war effort against the Axis. Puerto Rican New York was on the cusp of massive change: within a few years of her arrival came the beginning of Puerto Rico’s Great Migration to the continental United States: the world’s first massive airborne migration in history. Most Puerto Ricans migrating out of the island relocated to New York City.

Ironically, Puerto Ricans were pushed out of the island by the very political and economic changes so many had called for so long: political liberalization and economic modernization. Puerto Rico’s economy was rapidly modernized and industrialized, in a series of projects collectively known as Operación Manos a la Obra (Operation Bootstrap). The success of this modernization, however, was predicated on the massive migration of Puerto Ricans out of the island, as the new industrial economy was not able to provide the same number of jobs as the old agricultural economy. A policy of encouraging outmigration of hundreds of thousands was conceived as a kind of political safety valve to the massive unemployment. They were pulled into the American war effort, a dynamic that Dr. Edgardo Meléndez has called a “sponsored migration.â€

What Antonia Pantoja found within the growing Puerto Rican community must have deeply concerned her. Deep poverty, structural racism and discrimination, systemic violence, the disruption of the traditional family nucleus among families coming from the island, growing prejudice, inhumane housing conditions, rising rates of school dropouts, drug addiction, and many other problems plagued many new arrivals. She also found a migrant group that was by and large voiceless about the shape and direction of its own development in their new homeland. Pantoja responded to these conditions through a lifetime of institution building.

Pantoja’s institution building was based on a finely honed and original understanding of the historical development of the Puerto Rican and Latinx community in New York City. She saw this as a phased process. Puerto Ricans would gradually replace those from outside the community who had previously appointed themselves as spokespeople and instead claim their own voices, stabilized, and grew organizations, and finally created a new and original “Nuyorican†identity. She also used the consciousness of her own evolution as an activist and individual to inform her institution-building career.

Pantoja was a lifelong convener of groups and founder of organizations, though her institution building morphed along with the Puerto Rican’s community evolution, turning gradually more activist and militant. In 1957 she founded the Hispanic American Youth Association or “HAYA,†which later became the National Puerto Rican Forum, focusing on education and self-sufficiency. In 1961 she founded ASPIRA to focus on the education and leadership of young Puerto Ricans. In 1970, she created and subsequently led the Puerto Rican Research and Resource Center in Washington, D.C. One result of this project was the founding of what is now Boricua College in the early 1970s, which continues to cater to Puerto Ricans, Latinx, and other underrepresented communities in higher education through campuses in upper Manhattan, the Bronx, and Brooklyn.

A key point for Pantoja was access to language resources for Spanish-speaking Puerto Rican and other Latinx students in public schools. In 1972 ASPIRA brought a lawsuit demanding that the New York City Board of Education provide English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) in New York City classrooms. The result was a landmark piece of legislation in the bilingual education movement and one for which Pantoja helped pave the way.

It is impossible to imagine the founding and militant development of the 1970s Puerto Rican activist group the Young Lords Party without the previous work done by Pantoja. It is just as difficult to imagine the militant school-reform work of Dr. Evelina López Antonetty and her United Bronx Parents without the precedents Dr. Pantoja set. Similarly, the cultural awakening of a Nuyorican consciousness—a movement that took root in the mid-1970s, which proudly expressed the Puerto Rican urban migrant experience through artistic expression—is firmly rooted in the ever more militant work that she did. This Nuyorican cultural renaissance spread the influence of Pantoja’s organizing work around self-determination: work that was complex, nuanced, militant, sensitive to the needs of the Puerto Rican and Latinx communities of the city, but also fully imbued by the almost limitless possibilities provided by the rich and multicultural urban environment of New York City.

Over time, Pantoja also became more and more aware of how the complex dynamics of race issues among Puerto Ricans and Latinx communities led to differential treatment and access to opportunity according to skin color; accordingly, she began to openly identify more explicitly with the Afro-Caribbean roots of her own identity. In this and in so many other areas, Dr. Pantoja was a courageous visionary, for her explicit embrace of her own blackness and African roots opened the possibilities for a more frontal reckoning with racism within the communities of her concern, but also developed important institutional and activist bridges with the African American community during the post-Civil Rights era.

Pantoja was both a reflection and an engine of change with the Puerto Rican and Latinx community in New York. But her work also extended to supporting and reimagining Latinx communities beyond New York City. In 1978 she moved to San Diego, California, where she became an associate professor at the School of Social Work at San Diego State University. It was in San Diego that she met her partner of 30 years, Dr. Wilhelmina Perry; together they founded the Graduate School of Community Development in San Diego, In 1985 the couple moved back to Puerto Rico and where they established an intentional rural community – Producir – anchored on the ideas of productivity, cottage industries, employment, and local self-determination; Producir also founded a credit union bank in rural Puerto Rico as a means of supporting poor communities seeking greater economic opportunities.

\Pantoja returned with Perry to New York for her final years; her reputation and influence continued to grow. In 1996, President Bill Clinton recognized her efforts and dedication by awarding Pantoja the Presidential Medal of Freedom; she was the first Latinx woman to receive that honor.

Pantoja died in 2002 at age 80. After her death, her longtime partner, Dr. Wilhelmina Perry celebrated their relationship as a form of LGBTQ activism.

Famously smart, disciplined, and the possessor of biting sense of humor, Pantoja was also a true lover of all that New York City had to offer. She partook in many of the disparate types of communities who make our city their home, from bohemian artists in the Greenwich Village, to social workers in El Barrio/East Harlem; she was able to navigate and connect with the pursuits and aspirations of a truly diverse group of communities and people.

Today, ASPIRA continues to be a major non-profit organization serving the Latinx and other communities in New York, Puerto Rico, and several states along the eastern seaboard. For her work on behalf of all New Yorkers, but especially the Puerto Rican and Latinx communities of the city, Antonia Pantoja was truly both a champion and change maker.

Credit: Monxo López, Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Post-Doctoral Curatorial Fellow